My dad, Allan, died three days before Christmas. He’d lived with prostate cancer for 15 years – almost as long as I have lived in Australia. He chose not to have a funeral service, so in lieu of the public tribute I would have given, I’ve written this.

My dad always had a curious mind. I remember him borrowing a book from Greenock’s magnificent public library on how microwave ovens – in those days still relatively rare in domestic kitchens – worked. He hated when car engines changed from an easily take-apart-able mass of components to sealed black boxes that could only be fixed by a mechanic with a computer and a USB cable.

His love of meddling with machines saw him start his career fixing watches and clocks, then televisions, before joining IBM during the late 60s/early 70s heyday of tech. Never interested in managing people, he focused on his technical skills and worked latterly as a systems analyst, spotting bugs in programs the way I now spot typos in copy. He bought me a Commodore 64 computer the year everyone else got ZX Spectrums for Christmas because he wanted me to learn how to program in Basic, and in his view the Spectrum was more a toy than a PC. I learned a bit, but never could get my head round the binary numbers that he swore were so important in computing.

He took early retirement from IBM, younger than I am now, and dabbled in some freelance work. He was proud of his business name: ACE, for Allan Cowan Enterprises. Later, he’d design programs to remind mum when to take her medication. He once developed a hotel booking system for a non-existent client – just for the fun of it.

He had so many hobbies over the years. He rode motorbikes (until, I suspect, my mum told him to stop) and pushbikes; he windsurfed; had a dinghy and later a small boat. He took flying lessons and studied Spanish at night classes. He loved messing around with music on the computer, even writing a few of his own tunes that he edited to have applause at the beginning and end, and which miraculously appeared on the car stereo whenever he had a passenger. When I was making podcasts for one of my jobs, I started telling him how I was learning to use a particular piece of audio editing software: of course, he had already mastered it.

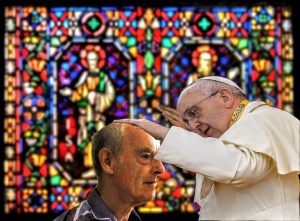

He enjoyed photography and playing with Photoshop, creating psychedelic effects on shots of local landscapes and once creating an image that showed him apparently being blessed by the Pope. He was slightly beyond Richard Dawkins on the atheist scale, but the idea of the photograph tickled him. On my last visit to see him I found a print of the image. I am also an atheist, but it’s going on my wall.

In front of the camera, too, his sense of mischief was always there. He found it almost impossible to pose with a straight face. In his own – and my – wedding photographs, he’s grinning and rarely looking at the lens.

He deliberately mispronounced the name of Scottish town Crianlarich so often that I genuinely thought it had a soft -ch (as in church) at the end, rather than the more likely sound you find at the end of loch. His musical training led him to call his house keys the clefs, an in-joke this budding language scholar and failed pianist thought was so clever.

He never lost the love of the Scottish mountains he’d had since his youth. Glencoe was his spiritual home, in particular the spectacular Buachaille Etive Mòr. For eternal atheist Dad, it was heaven on earth. He climbed alone most of the time, but loved exchanging stories with fellow devotees he met on the route. I never made it higher than the Water Slide – the start of his sacred Curved Ridge – but he taught me to ride a bike in the shadow of the mountain and as a family we spent many summer weekends trying to escape the swarms of midges that filled the air.

Music was another constant. The first record he bought was Diana by Paul Anka; he adored House of the Rising Sun by The Animals, Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells and Paul Simon’s Graceland. You Can Call Me Al on the latter particularly resonated, as he’d been called Big Al from Pilton by some colleagues back in the day. But it was the classical genre that he returned to every time: Chopin, Greig and especially Rachmaninoff (Rach 2 being a particular favourite). He played piano better than he would admit to, although preferred not to have an audience in the same room. In July this year I found myself with a spare ticket to see Sparks in Glasgow and insisted he come with me. He tapped along to the Mael brothers, who were almost the same age as him, but later admitted their electronic pop had done nothing for him.

After mum died, he struggled with living alone. He was never the best cook, but he kept the house neat and tidy, probably worried that if he didn’t, my mum would have something to say about it – although I wonder where he thought she was watching him from, given his lack of faith. Eventually he found an exercise class for older people (which he called his ‘jigging’ because they moved to music) and went as often as his health would allow. He never understood why his female companions never brought their husbands along – while at the same time (I suspect) relishing his position as the only man in the class.

While his progressing cancer miraculously caused very little pain until the end, he was frustrated by the growing weakness in his body and by the mild cognitive impairment he experienced. Just weeks before his death, when he could barely stand, he would say how he needed to get back to jigging, and express genuine surprise that he hadn’t managed a walk outside recently.

Like my mum, he didn’t want a funeral service. I hope it was because as an atheist, he didn’t want a minister of the church presiding over his final journey, and not because he didn’t think anyone would mourn him. Because we do.

- Happy to be marrying my mum.

- The last ‘serious’ shot, for his Blue Badge application.

- Watching his beloved Billy Connolly a few weeks before he died.